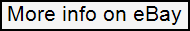

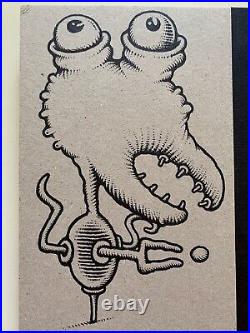

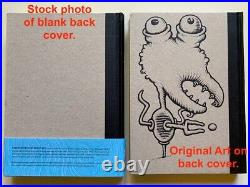

This Strangely Balanced Creature drawing was created several years ago. On a blank back cover of. Denis Kitchen’s Chipboard Sketchbook. But never offered for sale till now. As serious collectors know, Kitchen’s art very seldom is available. Prior to the more ambitious. Creatures From the Subconscious. (Tinto Press, 2023), DENIS KITCHEN’S CHIPBOARD SKETCHBOOK (2010) was the first collection of the artist’s peculiar drawings on “chipboard” that he drew below the radar for many years. Chipboard is the heavy, grainy card stock at the back of writing tablets. The artist started the habit of drawing on this unlikely substance during long, often boring production meetings at Kitchen Sink Press, his former publishing company, when he would flip his notes tablet over and doodle with a combination of the only tools at hand: a Sharpie pen and fine-point Uni-ball pen. With subject matter often extremely bizarre, or, in his own words, even “demented, ” Kitchen filed these away for many years. They were seen only his close friends and colleagues until this collection. Measuring 6 1/4 x 8 3/4 inches, the book features an extra thick 3 mm cover stock (chipboard, of course) with a de-bossed cover image and horizontal belly band. The full-color 128-page hardcover was edited and designed by Greg Sadowski and art directed by John Lind. The same pair won an American Graphic Design Award for their work on “Underground Classics” (by Kitchen & James Danky, Abrams, 2009). NOT suitable for children. Following on the heels of THE ODDLY COMPELLING ART OF DENIS KITCHEN, an overview of the pioneering underground cartoonist (Dark Horse Books, 2010), DENIS KITCHEN’S CHIPBOARD SKETCHBOOK is comprised of the peculiar drawings on “chipboard” that Kitchen has done below the radar for many years. Chipboard is the heavy, grainy card stock at the base of writing tablets. The artist started the habit of drawing on this unlikely substance during long, often boring production meetings at Kitchen Sink Press, his former publishing company, when he would flip his notes tablet over and doodle with a combination of the only tools at hand: a Sharpie pen and fine-point uni-ball pen. Denis Kitchen’s career began in 1968 as a self-published “underground” cartoonist. Mom’s Homemade Comics. This led to the formation of his pioneer publishing company, Kitchen Sink Press. For thirty years he published classic and underground artists alike, including R. Crumb, Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman, Milton Caniff, Al Capp, Scott McCloud, Dave McKean, Mark Schultz, Howard Cruse, Justin Green, Alan Moore, Art Spiegelman and Charles Burns. During these years Kitchen Sink won industry awards far disproportionate to its market share, sometimes more than any other publisher. In 1986 he founded and for its first eighteen years served as President of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, a non-profit organization dedicated to defending the industry’s First Amendment rights. After the demise of Kitchen Sink Press in 1999, his diversified activities include being a literary and art agent for a number of prominent clients and estates. Wearing a writer’s hat, he co-authored two books in 2009 for Abrams. The Art of Harvey Kurtzman. Both received award nominations and the latter won both an Eisner Award and Harvey Award in 2010. He is currently working on a biography of Al Capp. Dark Horse Books published. The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen. In 2010 and, in conjunction, a retrospective of his work was exhibited at New York City’s Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art (MoCCA) in 2010-11. Back cover text: Underground cartoonist and longtime publisher Denis Kitchen began drawing on the “chipboard” back of writing tablets during long, often boring meetings at Kitchen Sink Press, starting in the late 80s. These spontaneous drawings, done primarily with Sharpie markers and uni-ball pens, are distinctly surreal. The peculiar textured surfaces, unusual drawing tools, and possibly peeks into the artist’s id contribute equally to the unique look. After accumulating nearly a quarter century of these private drawings in drawers, Kitchen was persuaded by associates to publish the roughly 150 examples showcased within this book, presented with an introduction by the artist. Readers interested in seeing his better known art or learning about his diverse counterculture career should look at “The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen” (Dark Horse, 2010). Reviews: The aesthetics of a piece of artwork are informed by the medium it’s created with. The same drawing can take on different qualities on two different stocks of paper, or with two different grades of graphite. It’s the tactile aspect of art that doesn’t seem to get talked about much outside of art school. Fortunately, it’s front and center in DENIS KITCHEN’S CHIPBOARD SKETCHBOARD… The line work is remarkably effortless and whimsical and the drawings on the whole are hysterical; all the rubbery anatomy, devilish grins, and disturbing little beasties that are attendant when perusing a book of Kitchen artwork are on full display here… It’s really amazing to consider that all of these suitably bizarre pieces are drawn on the spot…. The shading, the proportion, and the pure comic bombast collected are an absolute pleasure to look at, and everything here provides further proof that Kitchen is a master cartoonist. –The Outhouse From the Introduction: MY PECULIAR FASCINATION WITH DRAWING ON CHIPBOARD By Denis Kitchen Sufficiently ancient readers of underground comix and some younger comix fans know that once upon a time I was a bona fide cartoonist. Though never exactly prolific, I debuted professionally in the late’60s with a solo self-published comic book. Mom’s Homemade Comics: Straight from the Kitchen to You. And for a short while managed to make a living just by writing and drawing funny pictures. But early in my cartooning career I joined the dark side and became a publisher. Soon the obligations of Kitchen Sink Press, consumed me. During the transitional period I managed to contribute short pieces and covers to a number of undergrounds and in the’70s I even did a weekly strip for a while and created numerous covers for alternative newspapers. Much of this has been collected in. (Dark Horse Books, 2010). But Kitchen Sink’s steady growth over thirty years, till its demise in 1999, made it increasingly difficult for me to find time to draw. I would periodically be lured or browbeaten by an outside editor but the literal cobwebs on the “assignments” thumb-tacked to my drawing board were the basis of running office jokes. It wasn’t that I didn’t. But the pressures of meeting a weekly payroll for as many as thirty employees, striving to meet scores of editorial and production deadlines every month and simply surviving in an intensely competitive market meant the Artist in me was of necessity subservient to the Businessman. I can’t speak for other cartoonists whose natural urge to draw takes a back seat to economic reality, but in my case, the practical outlet for that compulsive drive became doodling. As the head of Kitchen Sink, I was obligated to participate in seemingly endless corporate meetings, editorial meetings, marketing meetings, production meetings, planning sessions and so on. To some participants in those meetings I may have appeared rapt with attention at the head of the long table, taking “notes” on an ever-present writing tablet attached to a clipboard. And in fact I. Listening and participating with a reasonably large portion of my brain. But in reality the tablet was often flipped over and I was drawing on the side with “chipboard, ” the term printers use for the heavy cardstock forming the base of ordinary writing tablets. For reasons I can’t fully explain, I grew -and remain- quite fond of chipboard and its somewhat coarse, pulpy surface texture. My drawing tools were simple: a Sharpie pen for thick lines and a Uni-Ball Micro ballpoint for shading and more detailed noodling. That odd threesome -Sharpies, Uni-Balls and chipboard- grew at first out of convenience: they were all that I had in meetings. But then I maintained the combination from aesthetic pleasure. On several fundamental levels the art in this book, and certainly the technique, differs drastically from the art in the. When drawing commercial comics or illustrations for publication I first think of the idea/image, do thumbnails, then create layouts on a cold press illustration board. There the pencil lines can easily be erased until the preliminary outlines are satisfactory. I then carefully apply ink to the pencils using a Winsor & Newton Series 7 No. If a mistake is made, those inked lines can be covered with white correction paint and re-inked. To a confirmed “brush man, ” controlling the tip of the delicately tapered Russian fur is something akin to playing a finely crafted and tuned violin. My inking technique is by nature slow. I love to include fine detail, subtle shading and tiny elements that few readers ever see (especially when the larger images are reduced for publication). I take pride in most inked drawings and I certainly don’t intend to stop using a brush. But the drawings in this collection are polar opposites of my brushwork. One obvious distinction is the lower contrast between the natural color of chipboard and black ink in comparison to the harsh contrast of black on a pure white surface. The textures are likewise dissimilar. Under magnification the surface of chipboard looks like a choppy, stormy sea compared to the placid water of cold press illustration board. Most critically, my chipboard drawings are completely spontaneous, never conceived ahead of time and never penciled. I have no idea what I’m going to do when the Sharpie point hits board. That makes for exhilarating creative danger. If inking penciled under drawings with a brush is akin to following a musical score on a violin, then Sharpies on chipboard is more like drumming loose and free to a jungle rhythm. I allow my sub-conscious mind to take control, even as I’m consciously listening to someone drone on. Without preconceived direction, I will typically start with an abstract line on the chipboard. It might quickly evolve into a vague nose or an ear, but once that general direction is established I still do not know if the ear belongs to a human, a creature or neither. This stream-of-consciousness approach concocts images that often genuinely surprise me as the lines unfold. This form of self-entertainment is itself both incentive and reward. Because of the spontaneity of creation and the unforgiving nature of the pens, no “mistakes” can be erased. If I’m unhappy with an indelible line, I simply ignore it or work around the imperfection, often leading to new surprises. And since these mere doodles were never intended for publication (until now) and rarely seen by anyone, the immediate permanence of every stroke or stipple was never intimidating. Creating chipboard drawings is a distinctly liberating alternative to the planned, painstaking formality involved in creating comic art or illustrations. The latter are altogether different accomplishments but generally are more work than pleasure. Certain motifs reoccur in chipboard art that I cannot rationally explain: strange birds, gnarled wings attached to men and beasts, peculiar headwear, human feet on animals, devil horns, grimacing teeth and twisted limbs. I suppose on some level these uninhibited chipboard drawings could be a therapeutic release of internal demons. If so, they’ve conceivably saved me a small fortune in psychotherapy. But I prefer not reading any meaning whatever into images, whether recurring or singular. Sometimes a winged fish-headed man with horns is just a winged fish-headed man with horns, right? I used to feel a certain residual guilt about doodling during those company meetings. Could my apparent inattentiveness have contributed to the eventual collapse of Kitchen Sink Press? Those were genuine, if fleeting, concerns. But last year I ran across a reassuring tidbit in. It said studies demonstrated that doodling during meetings actually. In fact, according to the British study in. Doodlers retained 29% more information than non-doodlers tested in a control group. Sorting through more than two decades of accumulated chipboard drawings while assembling this book has actually inspired me to start drawing again in this manner. Now I keep the trusty trio of tools next to my living room easy chair and find myself frequently reaching for chipboard and Sharpie or Uni-Ball during boring TV shows and interminable commercials. Evidently boring company meetings are not a prerequisite for chipboard doodling. And as an unexpected bonus, compared to family members seated nearby, I retain 29% more of all infomercials.